A decade of population-driven demand built Canada’s housing boom. The immigration slowdown will now test how strong the market really is.

Table of Contents

For years, Canada’s housing story ran on one simple equation. More people meant more demand, higher prices, and an economy that looked stronger on paper than it felt in reality. The country’s growth engine was immigration, and for nearly a decade it powered everything from record rents to pre-construction sales. That model has now reached its limit. Ottawa’s 2025 federal budget marks the sharpest policy reversal in modern Canadian history, and it will change the housing market in ways that few people have prepared for.

The End of Population-Led Growth

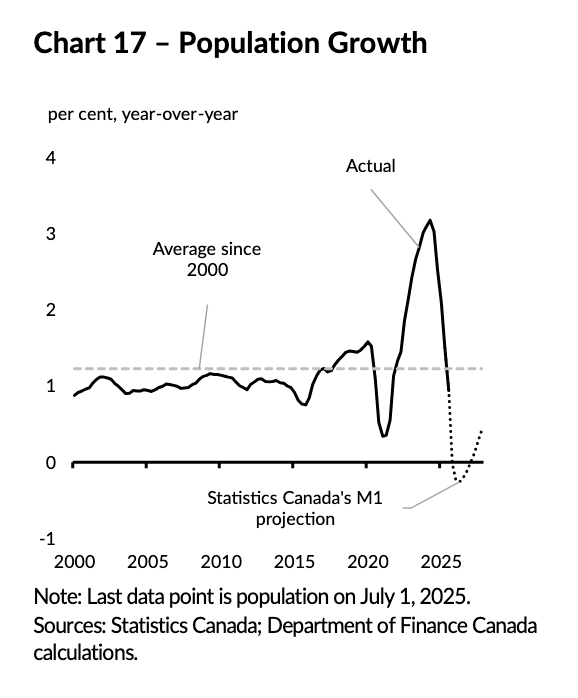

Between 2020 and 2024, Canada’s population grew by more than three million people (see the chart below). It was the fastest expansion in generations. Newcomers filled classrooms, rental apartments, and job openings that had sat empty during the pandemic. Then public pressure mounted over housing costs and infrastructure strain. The same government that built its legacy on immigration is now cutting intake so aggressively that Finance Canada projects population growth falling from above three per cent to nearly zero by 2026. Some forecasts even dip below zero.

Student visas will be reduced from about 305,000 to 150,000 next year. Permanent resident admissions are frozen at 380,000 a year until at least 2028, well below the previous target of 500,000. In practical terms, the flow of newcomers who once expanded Canada’s housing demand will slow to a trickle within two years.

How Immigration Became a Housing Policy Tool

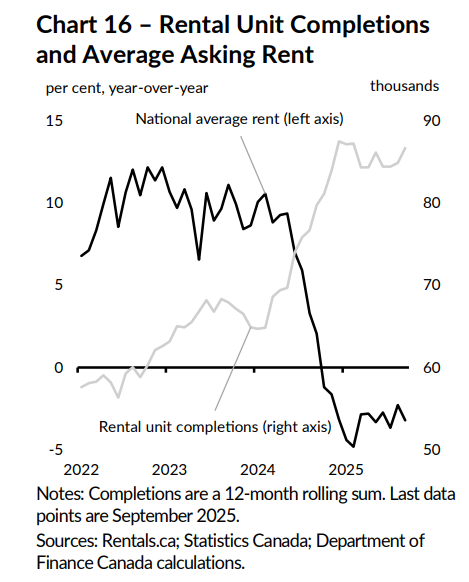

For most of the past decade, immigration was treated as a social good and an economic necessity. When construction lagged, population growth filled the gap in output by enlarging the workforce and sustaining consumption. The result was a housing system stretched beyond its limits. From 2018 to 2024, temporary residents rose from 3.3 per cent of the population to as high as 12 per cent. Rental listings disappeared, average asking rents rose at double-digit annual rates, and affordability metrics reached historic lows.

The Bank of Canada warned early that population surges were feeding inflation through rent and shelter costs. By the time policymakers reacted, vacancy rates had already collapsed. The federal budget now concedes that arrivals exceeded the country’s capacity to absorb and support newcomers. Immigration policy has effectively become a lever for housing stabilization, functioning alongside interest-rate policy as a tool to cool demand.

When the System Overloaded

The scale of temporary migration overwhelmed the infrastructure that supports newcomers. Healthcare, transit, and education all showed signs of strain. Fraud within the student-visa system deepened public frustration. Ottawa is now seeking authority to cancel visas tied to fake college networks and recruiter abuse. The policy shift may be rooted in fraud prevention, but its consequences will be felt across the housing market.

Ontario’s private-college sector expanded rapidly under provincial oversight, drawing thousands of international students whose tuition funded local institutions and off-campus housing. Those same towns are now facing empty rentals and declining enrollment. In many cases, population inflows had become a local economic dependency, supporting landlords, developers, and municipal revenues. The sudden reversal will be difficult to absorb.

A Structural Reset for Housing

Population growth accounted for nearly all GDP expansion between 2021 and 2024. Without it, the economy will have to rely on productivity rather than volume. That shift carries real-estate implications. Slower population growth means fewer renters and fewer buyers. Developers who planned projects around ever-rising absorption rates may struggle to secure financing. Pre-construction sales could weaken further.

At the same time, a pause in demand gives supply a chance to catch up. Builders facing labour and material costs that rose during the boom may find more stable conditions. Rent growth is likely to flatten as vacancy rates normalize. For the first time in a decade, the housing market could move toward balance through demographic change rather than monetary tightening.

The Policy Reckoning

Canada’s growth model relied on adding people faster than it added homes or productivity. GDP grew, but GDP per capita stagnated. On an individual basis, Canadians are no richer today than they were in 2016. The budget’s language around “sustainable levels” and “capacity to absorb” signals recognition of that imbalance. It also reflects a political recalibration. Public support for unlimited immigration has eroded, and policymakers now frame moderation as a measure of fairness, not restriction.

The adjustment will be painful. Sectors that depended on population growth, namely private colleges, small-town landlords, and consumer-goods retailers will feel the slowdown first. Yet over time, re-aligning population and housing supply may produce a healthier foundation for both affordability and productivity.

What Comes Next

If Finance Canada’s projections hold, the years ahead will look different from the last decade. Housing demand will cool, rents will stabilize, and the frenzy that defined the post-pandemic period will fade. The change will expose weaknesses that immigration once concealed, from construction bottlenecks to low labour productivity.

Canada’s housing model grew too dependent on perpetual inflows of people and capital. The system broke under its own weight. Now policy is forcing a reset. Whether that reset becomes a correction or a renewal will depend on how effectively the country rebuilds its capacity to house, employ, and retain the people it already has.

Note:

All charts in the blog are from the Canada Strong – Budget 2025 document.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is Canada slowing immigration?

To ease pressure on housing, infrastructure, and inflation after record population growth between 2020 and 2024.

2. How will this slowdown in immigration affect housing demand?

Fewer newcomers mean slower rental demand and weaker pre-construction absorption over the next two years.

3. Will home prices fall?

Prices may soften in high-growth markets, but most regions will see slower appreciation rather than a crash.

4. What happens to the economy?

GDP growth will cool as the economy relies more on productivity instead of population increases.

5. Is this permanent?

No. Immigration levels are frozen until at least 2028, giving time to rebuild housing and infrastructure capacity.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Daniel Foch is the Chief Real Estate Officer at Valery, and Host of Canada’s #1 real estate podcast. As co-founder of The Habistat, the onboard data science platform for TRREB & PropTx, he has helped the real estate industry to become more transparent, using real-time housing market data to inform decision making for key stakeholders.

Daniel is a trusted voice in the Canadian real estate market, regularly contributing to media outlets such as The Wall Street Journal, CBC, Bloomberg, The Globe and Mail, Storeys and Real Estate Magazine (REM). His expertise and balanced insights have garnered a dedicated audience of over 100,000 real estate investors across multiple social media platforms, where he shares primary research and market analysis.