Canada’s rental housing boom is solving scarcity in some regions but creating oversupply risks in others. Record construction, driven by CMHC’s MLI Select financing, has rapidly expanded supply, easing pressure for tenants. However, in smaller and mid-sized markets with aggressive pipelines, vacancy risks and investor strain are rising.

Table of Contents

Canada’s housing conversation has taken an unexpected turn. For years, the focus was on scarcity: too few rentals, too few homes, and too much pressure on tenants. Now, data from the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) shows that rental completions have hit a record high. For the first time in a generation, the question is no longer will we have enough rentals? but rather are we building too many?

This shift marks a new phase in Canada’s housing market. It is a story shaped by government policy, aggressive financing tools, regional imbalances, and the broader cultural divide between homeownership and renting. To understand what is happening, and where risks are building, Daniel Foch, our Chief Real Estate Officer (CREO) sat down with Brian Yu, Chief Economist at Central 1 Credit Union, whose recent report analyzes the scale and implications of this surge in rental supply.

Canada’s Rental Construction Hits Record Levels

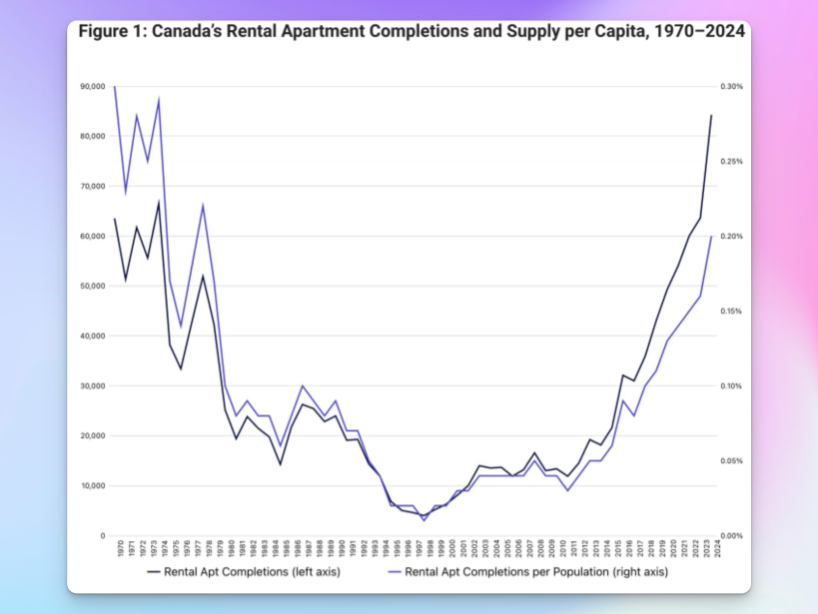

The numbers tell the story. CMHC data shows that Canada is building more rental housing now than at any point in modern history. On a per capita basis, the country is approaching the record pace last seen in the 1970s.

That comparison matters. In the 1970s, Canada built a massive stock of rental apartments. But by the 1980s and 1990s, policy shifted to favour homeownership. Incentives tilted toward buyers, and rental construction slowed to a trickle. For decades, purpose-built rentals were a forgotten segment.

Fast forward to today, and the pendulum has swung in the opposite direction. Rental apartments now make up the majority of new housing under construction. Canada has effectively re-engineered its housing pipeline, and the results are finally visible in the numbers.

The Role of CMHC’s MLI Select

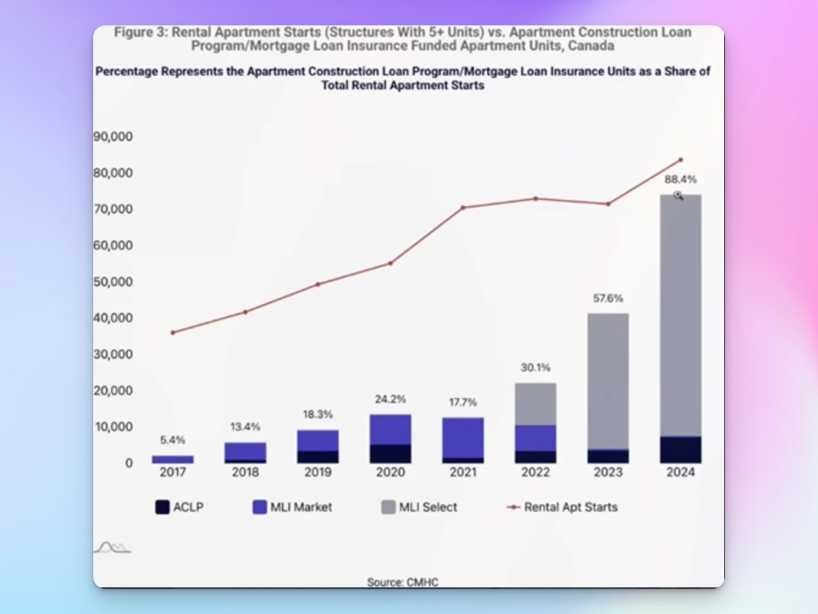

This surge has not happened by accident. Almost 90 percent of new rental starts are being financed through CMHC’s MLI Select program.

The mechanics are straightforward but powerful. MLI Select offers developers access to unusually favourable financing:

- Extremely high loan-to-value ratios (up to 90 percent).

- Very long amortizations (as much as 50 years).

- Low debt service coverage requirements.

In practice, this allows developers to borrow heavily and take on projects that otherwise might not pencil out. From a policy standpoint, this was the intended outcome. Canada needed more rentals, and this program delivered them.

But there is another side to the story. By making debt cheap and accessible, MLI Select has encouraged developers to stack leverage on thin margins. Many projects are only modestly cash-flow positive, kept afloat by long amortizations and high leverage rather than robust rental income. This creates systemic risk if rents fail to meet expectations.

The Risks of Oversupply

The risk is simple: too much supply at once.

If a surge of new rentals arrives in markets without corresponding population growth or household formation, the balance shifts quickly. Vacancy rates rise, rents soften, and landlords’ income shrinks. For highly leveraged operators, that shift can turn into financial strain.

This is the scenario beginning to take shape in parts of Canada. For tenants, it is a welcome reprieve. More vacancies mean more choice and, eventually, more affordable rents. For investors and landlords, it is a very different story: thinner margins, slower lease-ups, and the possibility of operating at a loss.

CMHC’s Safeguards

Recognizing these risks, CMHC has introduced safeguards into MLI Select. Two stand out:

- Liquidity Requirement: Developers must now hold at least 25 percent of project costs in liquid or liquidable assets. This ensures that if rental income falls short, there is a buffer of equity behind the project.

- Rental Achievement Holdback: Loan sizes are adjusted downward if completed projects fail to achieve the rental income forecasted at application. If a project was underwritten for $100,000 of expected income but only generates $80,000, CMHC will reduce the loan by 20 percent. Developers must either inject more equity or secure secondary financing to close the gap.

These measures protect CMHC and lenders, but they do not eliminate risk for landlords and operators. If rents disappoint, it is the owner’s balance sheet that absorbs the shortfall.

Market-by-Market Risk

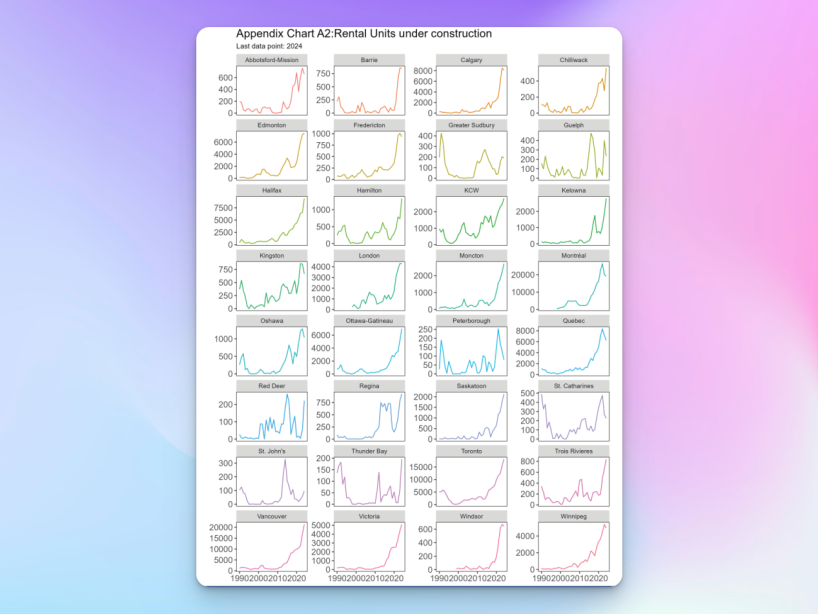

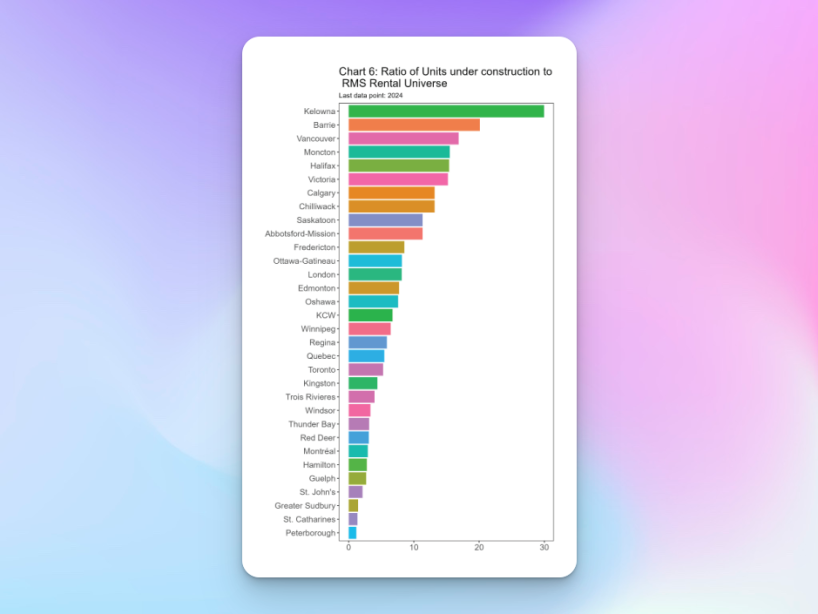

The national picture masks sharp regional contrasts. Brian Yu’s analysis looks at the ratio of units under construction relative to total rental stock in each market. This ratio reveals where oversupply risks are highest.

- Kelowna: Nearly 30 percent of existing rental supply is matched by units under construction. Without rapid population growth, this could push vacancy rates sharply higher.

- Barrie, Vancouver, Halifax, Moncton: Roughly 15–20 percent of rental stock is under construction, a substantial injection of supply that could destabilize local markets.

- Calgary, Saskatoon, Prairies: Elevated levels of construction relative to demand.

- Larger metros like Toronto and Montreal: Lower ratios relative to overall rental stock, creating more room to absorb new supply.

The conclusion is clear: risk is not evenly distributed. Smaller and mid-sized markets with ambitious pipelines may face far greater volatility than the largest urban centres.

Canada as a Rental Nation

The current wave of construction carries cultural meaning as well as economic weight. For decades, homeownership was treated as the cornerstone of financial security in Canada. It served as a form of forced saving in a country where households often struggled to build wealth through other means.

Today, that cultural script is under pressure. With renting now representing a record share of new housing construction, Canada is moving closer to a renter-oriented model.

This raises uncomfortable questions. Is homeownership really synonymous with freedom? Owners face property taxes, land transfer taxes, and illiquidity if they need to move. Tenants, by contrast, may enjoy greater mobility and lower transaction costs.

For tenants, the new supply is unquestionably positive. More rentals mean more bargaining power, more choice, and in many cases, lower costs. For landlords, it means competing in a market that is no longer defined by scarcity.

Conclusion

Canada’s rental housing market has entered uncharted territory. From decades of undersupply, the pendulum has swung to the risk of oversupply. In some cities, nearly a third of the existing rental stock is mirrored by projects under construction.

The outcomes will not be uniform. Some regions can absorb the wave, others may see vacancies spike. For tenants, this is a rare moment of relief in a market long defined by scarcity. For investors, it is a reminder that leverage cuts both ways.

The broader lesson is that policy works, but sometimes too well. By aggressively financing rental development, Canada has built the supply it demanded. The next phase of the story will be defined by how markets, landlords, and tenants adjust to that abundance.

Valery AI is trained on Daniel Foch’s insights and the latest market data to show you exactly how today’s shifts affect your numbers, risks, and opportunities. Get your Personalized Real Estate Playbook now.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is driving Canada’s rental housing boom?

Canada’s record climb in rental housing is largely fueled by CMHC’s MLI Select financing program, which offers developers high leverage, long amortizations, and favorable borrowing terms that make projects viable.

2. Could Canada face an oversupply of rental housing?

Yes. While rental scarcity is easing, some markets, especially smaller and mid-sized cities, risk oversupply, leading to higher vacancies and downward pressure on rents.

3. Which Canadian cities are most at risk of rental housing oversupply?

Kelowna, Barrie, Halifax, Moncton, and parts of the Prairies face elevated risk, while larger metros like Toronto and Montreal are better positioned to absorb new supply.

4. How does the rental housing boom affect tenants and landlords?

Tenants benefit from more choice, lower costs, and stronger bargaining power. Landlords and investors face thinner margins, slower lease-ups, and potential financial strain in oversupplied areas.

5. What safeguards has CMHC added to prevent rental housing risks?

CMHC now requires developers to hold 25% of project costs in liquid assets and adjusts loan sizes based on actual rental income performance, ensuring some buffer against financial shortfalls.

About the Author

Daniel Foch is the Chief Real Estate Officer at Valery.ca, and Host of Canada’s #1 real estate podcast. As co-founder of The Habistat, the onboard data science platform for TRREB & Proptx, he has helped the real estate industry to become more transparent, using real-time housing market data to inform decision making for key stakeholders. With over 15 years of experience in the real estate industry, Daniel has advised a broad spectrum of real estate market participants, from 3 levels of government to some of Canada’s largest developers.

Daniel is a trusted voice in the Canadian real estate market, regularly contributing to media outlets such as The Wall Street Journal, CBC, Bloomberg, The Globe & Mail, Storeys and Real Estate Magazine (REM). His expertise and balanced insights have garnered a dedicated audience of over 100,000 real estate investors across multiple social media platforms, where he shares primary research and market analysis.